My close friendship with the celebrated guitarist is something else. So is he.

By Martha Frankel

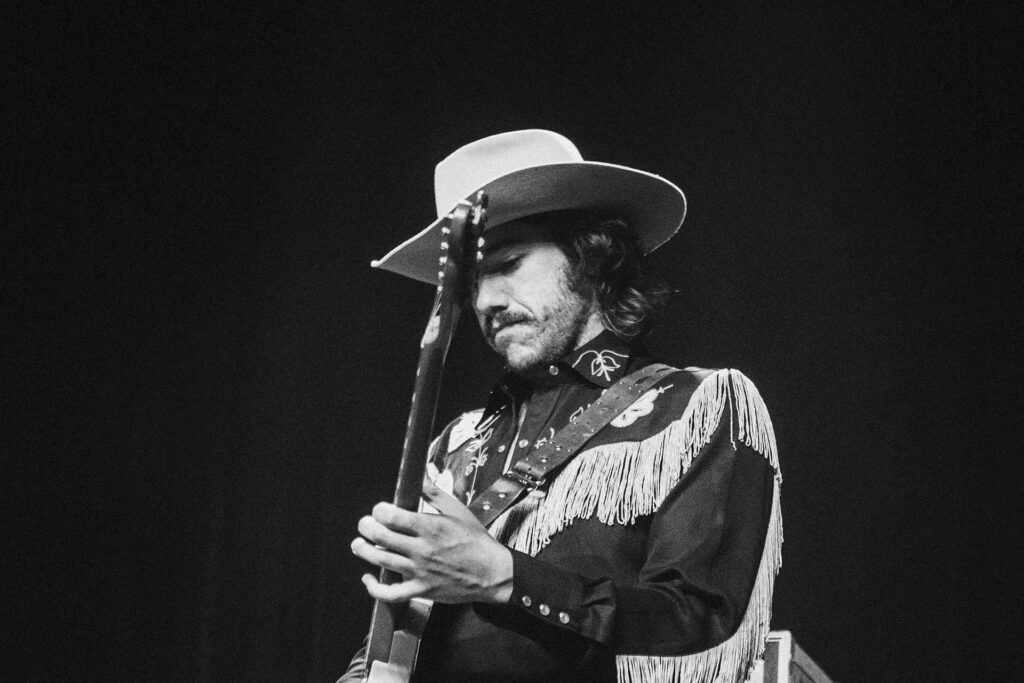

Photography by Fletcher Moore

You know what you should do?” he texted. It was the spring of 2019. Winter was just fading. “Come out here to Vegas!” He was my pal Connor Kennedy, the guitar virtuoso who would turn 25 a few months later.

I laughed. I’m an addict in recovery. Part of my addiction, which I chronicled in my memoir Hats & Eyeglasses, was to online poker. And although I sometimes play live poker, Las Vegas isn’t a good place for someone like me, someone prone to excess, someone who thinks 3:30am is prime decision-making time. “That’s not gonna happen, boychick,” I texted back.

Connor was in Vegas for a three-month residency, playing guitar with Steely Dan. It was a dream job. More than that, even. But he was alone a lot and wanted company. “My hotel doesn’t have a casino,” he texted a few nights later. “It’s where all the musicians stay. The rooms have nice little kitchens. I bought a cast iron pan. I’ve been making steaks.”

I laughed. Food was our language. And a good steak never hurts. But I forgot about it, and him, for a couple of days. Then I got this text: “Please come. I’m losing my mind. Everyone else in the band goes home when we’re not playing. Vegas isn’t a good town to be alone. Plus, I found the greatest breakfast place, off The Strip, with the best iced coffee and the most incredible savory porridge.”

I could say I booked the trip because he was losing his mind, but congee for breakfast is my dream. And he knows it. I booked a flight that night. He picked me up in a Mustang convertible, and that car set the tone.

If you’ve ever been near Connor, you know this—he’ll find the best restaurants in any town he’s in. He’ll know the food scene better than the locals after a week. When on tour in 2017-19, he went to every barbeque joint he could find. He met the pit masters. He got schooled in vinegar mops.

So, in the Vegas mornings we went to his breakfast spot and damn, he was right. In the afternoons, we drove deep into the desert. Or into the neighborhoods where “real” people lived. We found the Asian section of town and bought him an enormous molcajete (a mortar & pestle) that would come back to Woodstock with his guitars. We went to Pok Pok for Chef Andy Richter’s wings. We stopped at Eataly to discuss steaks. We went to dinner at Roy Choi’s Best Friend, where we basically—and happily—ordered everything on the menu. On our last night I went to The Venetian to see Connor play with Steely Dan. On the way through the hotel, I had a full-blown panic attack. I couldn’t tell if the clouds were a glimpse of the outside or painted on the ceiling; if the people in the gondolas were real, if the sounds were birds or slot machines. Connor saw it happen and didn’t say a word, just strode behind me, put a hand on my waist and propelled me forward. He sat me at the first slot machine we came to and just stayed with me ’til I could breathe again. We never talked about it again.

That winter my husband Steve Heller and I were in Los Angeles and Connor was, too. In the mornings during our stay, he’d leave involved texts about where we should eat and what we should order. This guy definitely works best with a set list.

Steve and I decided to leave LA a week early. It was clear something was happening in Europe, and it sounded scary. I mentioned to Connor that he should either get a place for a month (he’d been staying at a friend’s guesthouse) or come home. “Really?” he asked over and over.

By March 10 there was no denying it. And a couple of days later he started the drive back across the country. “No one’s on the road,” he texted from each state.

In the summer of 2020, when it was clear musicians wouldn’t be touring or playing live in concert anytime soon, he approached Steve about building a barbecue smoker. They worked on it for more than a month. Connor moved it to Mount Tremper, to Catskill Pines, where he served a once-a-week, always-sold-out outdoor barbecue that was invariably the talk of the town.

A few months ago, he called to talk about Ken Burn’s country music documentary. “It’s like 30 hours long,” he said. The next day he asked if I was ever in the VFW on Albany Avenue in Kingston. I had. “It’s a great room,” I said. Within days he had booked it for every Wednesday in April for honky-tonk. It was Connor and the guys he’s been playing with for a decade: drummer Lee Falco, bassist Brandon Morrison, keyboardist Will Bryant, plus the incandescent Cindy Cashdollar on pedal steel. The second week they put up a disco ball and turned down the lights. Week three they hired a dance instructor and people started driving from as far away as Boston to two-step around. It got extended into May and then through June. Who knows, it might still be happening!

Now, when he texts and says, “You know what you should do?” I just throw my hands up and say, “Whatever you tell me.”

Comments are closed.