The amorality of aesthetics with Archie Bunker, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Barbra Streisand and, yes, Madonna.

By Kevin Sessums

During the first season of All in the Family in 1971, its Episode 5 was titled “Judging Books by Covers.” Its story line was a gay one concerning Archie Bunker’s homophobia and his having to face the fact that his bar buddy, Steve, an ex-pro football player and linebacker who owned a camera shop down from the bar foreshadowing Harvey Milk’s opening his the next year, was gay himself. I was 15 years old and just beginning to deal consciously with the actuality of my own gayness. That episode of All in the Family made as an indelible emotional and psychological impression on me as Archie’s derrière did in a physical way on his famous chair on which he sat and spewed his scripted bigotry as perfectly spaced punchlines each week as the sitcom contextually debunked his Bunker mentality. That chair now sits itself at the Smithsonian where it proves the importance of the metaphoric “furniture of home,” as Auden wrote of more than its comfort in his “September 1, 1939,” but also of its own contextual need in the larger design of life and history, a harboring of hope where the direness of derrières—humanity more haunch than homily—rested, steadfast in their unsteadiness, on bar stools homing in on the fierce resolve of the familial no matter how far we stray from our selves toward the collective self.

In that same All in the Family episode, Archie’s wife, Edith, expounds in her batty way about the existential bounds of photography when shown some vacation snapshots of a luncheon guest who had just visited London. She talks about her fascination with the idea that posing for photographs momentarily suspends time and allows those posing to pause their haunched humanness which then inspires her oddly moving, yes, poetical homily. Bunker arches his Archie eyebrow at her musing. “You’re a pip,” he says. “You know that Edith? You’re a regular Edna St. Louis Millay.” The audience laughs at his latest malapropism, getting the reference to another poet, Edna St. Vincent Millay, proving not only its own erudition but also how Millay was still so well-known that she could be referenced as a joke on a sitcom. I wasn’t sure who she was myself when I was 15 so later went to look her up at the library and have been fascinated by her ever since.

Norman Lear, who co-wrote the episode, knowingly put the reference in Bunker’s bit of dialogue because Millay—known to her friends as Vincent—was a bisexual and an exponent of free love in the 1920s. She and her husband, wealthy Dutch coffee importer Eugen Jan Boissevain, were quite forthright about their open marriage after having met at a party at Croton-on-Hudson and partnering in a game of charades. He was the widower of labor lawyer and war correspondent Inez Milholland, a political hero to Millay whom she had met during her studies at Vassar. Both Boissevain and Millay were early feminists and he tended to household duties at their country estate Steepletop in Austerlitz so she could devote herself to her writing. Although she had been a tenaciously vital star presence in the partying Greenwich Village of artists and activists of the times roaring about her—“My candle burns at both ends;/it will not last the night;/But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—/It gives a lovely light!” she famously wrote in her quatrain “First Fig” published in the June 1918 issue of Poetry magazine—she also had longed for a roomier, more ruminative place where she and her imagination could roam as they had in coastal Maine where she spent so much of her impoverished childhood with her two sisters and single mother. “I cannot write in New York,” she told a reporter from Boston’s Sunday Globe in 1925. “It is awfully exciting there and I find lots of things to write about and I accumulate many ideas, but I have to go away where it is quiet.” So, she and Boissevain, having lived for a couple of years at 75 1/2 Bedford Street in what is still known as the “skinniest house in New York” measuring only 9 feet 6 inches wide, bought the 435-acre blueberry farm for $9000 after seeing an ad for it in the New York Times, later purchasing an additional 300 acres adjacent to the property so that they could own the whole of the mountaintop.

In the Stories section at the Vassar website, Holly Peppe, the Literary Executor of her estate, writes of its alum, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry: “Over the next several years, Millay and Eugen transformed the property into an elegant country estate with flower, herb, and vegetable gardens; guest houses; a tennis court overlooking the Berkshire hills, and a sunken garden area in the foundation of an old barn consisting of garden rooms separated by stone walls and arborvitae hedges.”

If books can be judged by covers, a person can be discerned by the decoration and design of one’s rooms—especially the conceptual sort separated by doors built into the natural landscape between trees through which such “garden rooms” flowed in a kind of structured wildness which mirrored Millay’s own.

When the poet and her husband bought their Upstate mountain home it still had the vestiges of the Victorian about it, so she set about to both honor its foundational functional aspects while reimagining them in ways that better suited her reimagined self. In the same way she subverted the strictures of her lyrical poems, which were so often built upon the structures of the sonnet and rhyming couplets and quatrains, with her insistence that female sexuality was a worthy subject to be contained within them and thus incongruously unleashed, she brandished her bohemianism as a kind of aesthetic that lived side by side with her longing for the rustic, rambling comfort of an Upstate farmhouse built upon the architectural bones of the Victorian ardor for order. For example, the freshwater pool on the property which was filled from a spring-fed cistern up-mountain, could only be used by swimmers who swam unashamed in the nude and shunned any need for a bathing suit based on her bare-derrières edict even though there were separate outdoor dressing rooms for men and women with cast iron dressing tables.

Millay also wrote in her diary, “Did all my weeding without a stitch and got a marvelous tan.” And yet she and her husband, as was the custom of the time in households of a certain strata of society, dressed for dinner each night and were served by a maid and butler. They would then retire to either their separate bedrooms upstairs, an interior landscape of their open marriage where they could welcome their respective lovers, or to the “withdrawing room” as Mark O’Berski, Vice-President and Treasurer of the Edna St. Vincent Millay Society at Steepletop, referred to it when giving Kendra Gaylord a tour of the home and its grounds for her podcast Someone Lived Here. He continued: “What’s very unusual for a Victorian farmhouse is that the size of this room is enormous. It used to be two rooms, as there would have been in a Victorian house, two front parlors. And they had the wall removed so that Millay had room for two grand pianos. Because she liked to play duets with friends. So over here, this is Millay’s piano. It’s a Steinway from 1925. No one was allowed to play this except Millay.”

She also seldom allowed others to sit in her favorite chair which she referred to as her “bird window seat.” She would place a tray of bird seeds right outside the opened window and wait for the arrival of alighting birds, many of which would enter the room next to her, where she sat keeping her bird journal. But her favorite room—her inner sanctum—was her upstairs library which still contains over 3000 books. Millay was fluent in seven languages and many of them are in French, Spanish, Latin and Greek. The sections are organized, among others, into classics and Shakespeare and fiction and women’s rights. She did a lot of her reading and writing lying on a daybed situated in front of a table that held more books and a large globe that anchored the room. Above it all hung a sign, another edict from her: SILENCE.

The kitchen, unlike the library, was not her domain—her husband and servants did their cooking chores there—but it was where she was found after her death lying on its floor having fallen down the stairs and broken her neck after a heart attack, according to the coroner’s report. It was only a year after Boissevain had died of lung cancer in 1949. The scales in the pink bathroom upstairs are still set to 98 pounds, which is what the 5-foot poet weighed when she died. She and Boissevain are buried side by side on their mountain in Austerlitz.

Indeed, all of us writers know that the description of rooms whether imaginary ones in novels or real ones utilized as reportage in biographies or profiles written for magazines can be a kind of forensic tool itself in delving into the discernment of character without having to make moral judgments in doing so since aesthetics on their surface are amoral, the chosen surface of one’s life being finally what they are only about. But they give us hints. They help us, yes, home in.

When I was writing a cover story in 1991 on Barbra Streisand for Vanity Fair, she invited me into her Beverly Hills mansion on one of the days we were having our many conversations. At one point she was describing her New York City apartment to me—it once had belonged to lyricist Lorenz Hart who lived there with his mother—saying she had decorated it “in chintz and Chippendale and 18th-century furniture. When I was playing Fanny Brice I used to make fun of her taste, you know, when I was on the set of the movie. ‘How can she live in this fancy stuff?’ I used to ask our director, Willie Wyler. Now my apartment has furniture with Queen Anne legs, and it looks like the sets for Funny Girl.”

“Taking me on a tour of her Beverly Hills home,” I continued, “the inveterate collector and renovator tells me that when she can find the time in her schedule she plans to build her own version of an antebellum mansion on another plot of land in Beverly Hills. For now, however, she has busied herself with decorating this house, which she’s recently cleared of the Art Nouveau and filled with furniture by Frank Lloyd Wright and Gustav Stickley. Many of the pieces, Streisand is proud to point out, were owned and used by the two Arts and Crafts designers themselves. Drawings by Gustav Klimt hang next to disquieting nudes by Egon Schiele (holdovers from her Art Nouveau phase), but two Edward Hoppers have been added to the collection to complement the Arts and Crafts pieces. As we sit on facing couches in the living room, a bust of Sarah Bernhardt, sculpted by the divine Frenchwoman herself, stares at us from across the room.”

Later that day, she offered to take me upstairs to her study where portraits of her family, surrogate and otherwise, were kept so she could play me a tape of the then 13-year-old Streisand singing “You’ll Never Know” in a duet with the adult Streisand as the real Streisand sat in the overstuffed chair behind her desk and, glancing down at a perceived imperfection in one of her fingernails, lip-synched with herselves—or, I see now, created in real time for me the collective self as she, a manifested metaphor (which all stars are) sat more precisely within her own version of Auden’s “furniture of home.” She had made me promise, however, that I wouldn’t write any descriptions of her bedroom we had to pass by to get to her study since she innately knew that writing about that interior would give her public a few too many intimate hints about who she might be. I promised before she allowed me up.

“On the wall next to the stairwell,” I wrote as we climbed toward her own inner sanctum, “across from another Klimt and a small portrait by Tamara de Lempicka, are three gigantic Mucha theatrical posters advertising Parisian productions starring Sarah Bernhardt. ‘These are the only posters I’ve ever bought, because they are the three roles I have always longed to play,’ she tells me. ‘Camille and Hamlet and, especially, Medea. I did Medea when I was 15 in acting class in New York, and I still think it is my best work. I’ll always remember one of her lines: “I have this hole in the middle of myself.”’

The year before, my first cover story for Vanity Fair had been on Madonna who also had a home filled with art. This was my lede: “You reach the house by driving up into the Hollywood Hills as far as you can go. It is, of course, At the Top. Like Madonna herself, it is surprisingly small, startlingly white, all modern angles and hard edges. Everywhere, there is an exquisite incongruity. Outside, a black Mercedes 560SL is parked next to a coral-colored ’57 Thunderbird; inside, twentieth-century art performs a visual pas de deux with eighteenth-century Italian furniture. Catholic candles, tackily embossed with saints, dot the house’s sophisticated rooms. On a kitchen counter, audiotapes of Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth lie stacked beside rap tapes by Public Enemy.”

Later in the story, I continued with my description of the interiors—and thus her—as she gave me a tour of her home: “Outside her bathroom, hung on the wall above a Nadelman sculpture, is the photograph given to her on her 31st birthday by Warren Beatty. It is a picture by Ilse Bing of a group of women in diaphanous gowns caught performing a la Matisse’s The Dance. She points to the woman whose head is thrown farther back than the others’, her hands not exactly clasped in the thrall of collaboration. The woman obviously wants the attention all to herself, and Bing has captured that blissful desire perfectly. Madonna tilts her head at the same angle and breezes past the photograph. ‘Warren says she reminds him of me. I don’t know why.’

“We circle back to the main room,” I wrote toward the end of the detailed tour she had given me that day. “An ornately gold-framed Langlois, originally painted for Versailles, is as large as the entire ceiling. And that is exactly where Madonna has hung it, Hermes’ exposed loins dangling over our heads. Above the fireplace is a 1932 Leger painting, Composition with Three Figures. Across from it is a self-portrait by Frida Kahlo, the legendary Mexican artist and revolutionary. Another wall holds a nude painted by Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera. Boxer Joe Louis, photographed by Irving Penn, pouts in a corner across from Man Ray’s nude of Kiki de Montparnasse. All around us are other photographs taken by masters, new and old: Weston, Weegee, Tina Modotti, Matt Mahurin, Lartigue, Drtikol, Blumenfeld, Herb Ritts.

“In the entrance foyer is another Kahlo, titled My Birth. The small painting depicts Kahlo’s mother in bed with the sheets folded back over her head. All that can be seen of the mother are her opened legs, the head of the adult Kahlo painfully emerging from her mother’s gaping vagina. There is blood in the painting. There is anger there. Sorrow. “‘If somebody doesn’t like this painting,’ Madonna says, ‘then I know they can’t be my friend.’”

I did like the painting. But I never became her friend. Because the design of a home—the private choice of art and furnishings and even the placement and alignment of it all—tells a visitor a version of the truth as it also knowingly lies. Our aesthetics are the story we tell ourselves about who we long to be even if we have a long way to go to being that person. Aesthetics are neither right nor wrong because good taste and bad taste are finally not about goodness or badness. They just lay out a pathway paved with the need to be perceived as a certain kind of person. The discernment is discovering not what lies beneath the surface but seeing where instead it leads.

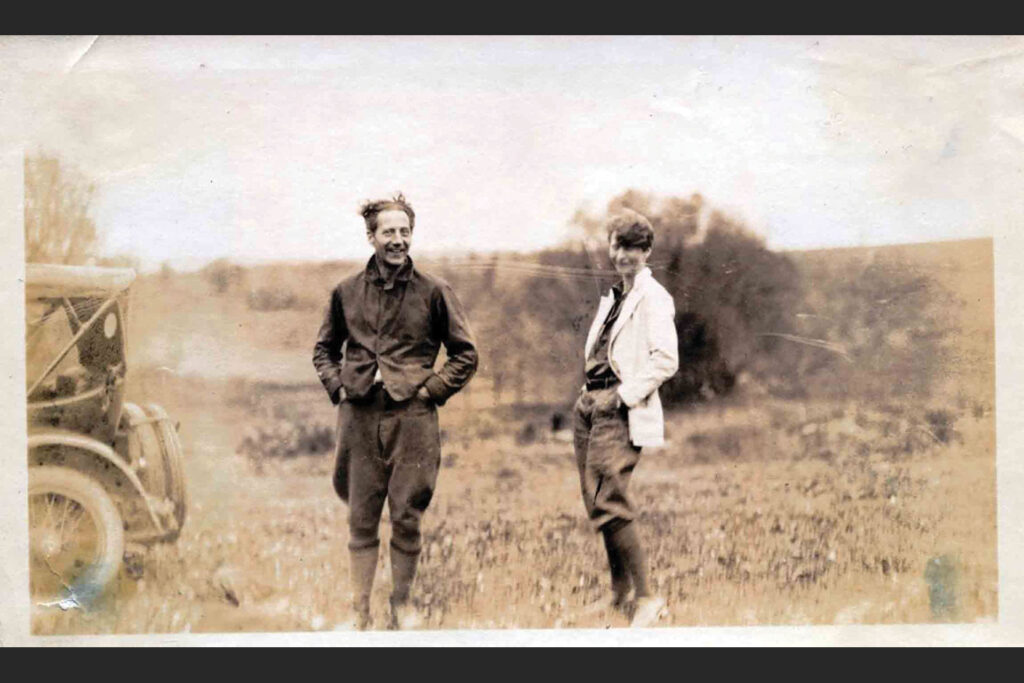

dead poets society (above) Famed American poet—and subject of a classic Archie Bunker punchline—Edna St. Vincent Millay and her dapper husband, Eugen Jan Boissevain, at their beautiful home Steepletop, in Austerlitz, NY in 1925. (Millay Society)

Comments are closed.