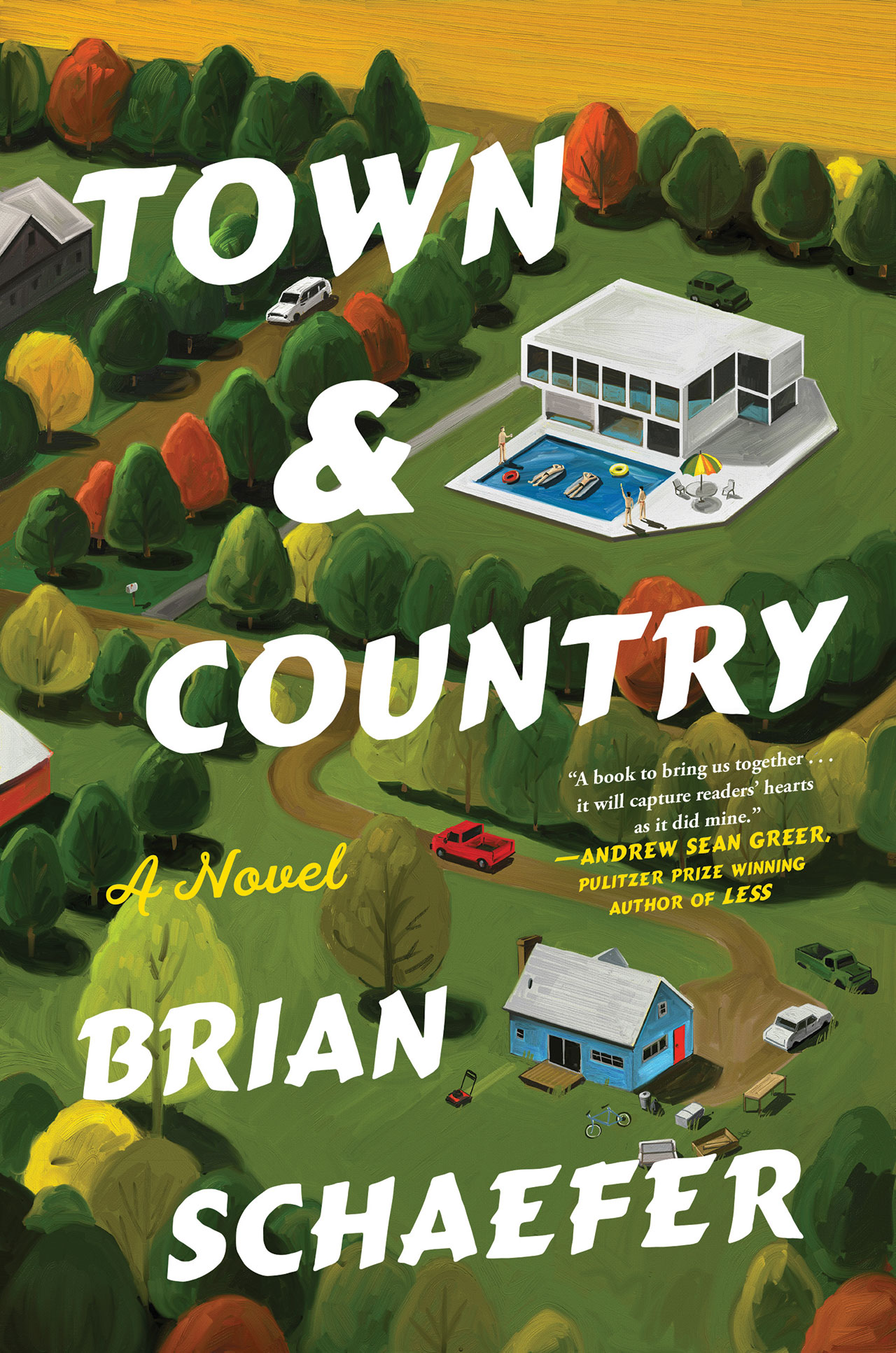

In Town & Country, Brian Schaefer’s keenly observed debut novel, pink polos upend not only real estate prices but the very idea of belonging.

By James Long

Like many before me and since, I spent summer weekends on Fire Island Pines—a feverish, salt-air season that glows in my memory like a sun-faded photograph.

Every Friday, I joined a bevy of gay men fleeing New York City for the barrier island’s wooden boardwalks and dune paths, where Speedos were less suggestion and more necessity and the weekends were choreographed for pleasure. I shared a weathered cedar house with several friends, all of us single and young enough to mistake our self-indulgence as a permanent escape. On one memorable après-beach afternoon, we hosted what I would grandly describe as a Dionysiac sarong party. Inviting friends from other houses—and newly minted “friends with benefits,” like seashells, collected from the beach—everyone came wrapped in a length of bright cloth knotted at the hip, their glistening tanned torsos bare. Accessories of beads, rhinestone tiaras and feather boas were nearly as loud as our stereo (or was it a boom box?) blaring a Pet Shop Boys cassette from the deck. Someone snapped Polaroids—too many, maybe—and they remain with me still, a shoebox archive of youthful excess and the fleeting ease of those weekends.

One might imagine how my chronicle stretched into the future—a scenario delightfully rendered in Brian Schaefer’s sharp debut novel, Town & Country (Atria Books). The gays are older; some are gone, lost to AIDS before the pills arrived, others married thanks to laws that finally caught up to reality. Their careers secured and their wallets heavier, they traded Fire Island shares for farmhouses, fixer-uppers and Gothic revivals, their NYC polish seeding gentrification in trendy rural towns and hamlets: another kind of Pines invasion, quieter but no less transformative. And, as Schaefer’s prose artfully captures, no less contentious.

Town & Country takes place in Griffin, a rustic township whose watchful inhabitants see a threat from afar, like the mythical creature that shares its name. Part of a swing district heading toward a congressional election in six months, Griffin finds itself caught between shifting allegiances—between lifelong townsfolk and the pink-polo-wearing “power gays,” to whom Schaefer bestows other clever taxonomic classifications I won’t spoil—the latter’s influx driving up real estate and remaking its streets into expensive gourmet-this and boutique-that, gourmandizing salmon-dill canapés and poolside bottles of rosé.

The Griffin gays have also registered to vote—and therein lies the battle. One of their own, Paul Banks, is running for the House seat, his campaign bankrolled by his older husband Stan, whose private grief shadows Paul’s public ascent. On the opposing side is Chip Riley, who owns the local pub—a gathering place largely unchanged over the years. His wife, Diane, a devout Protestant and real estate agent, is grappling with a “both saint and sinner” tug-of-conscience: once leading a crusade against same-sex marriage, she’s now selling homes to the “impossibly plural” gay transplants.

Schaefer is a character virtuoso, populating Town & Country with figures who are at once recognizable and wonderfully unexpected. Add to the novel’s intrigue two Riley sons: Will, a college student fresh out of the closet, and his older brother, Joe, struggling with addiction over the death of his best friend; the self-loathing Leon Rogers whose calculated moves to be accepted by the in-group backfire; and Eric Larimer, whose unlikely bond with a late-twenties farmer is a window into the region’s complicated soul.

Harkening back to my summers on Fire Island, it feels as mythical now as Schaefer’s intrepid Griffin. Both places, real or fictional, wrestle with their own kinds of elections—what it means to belong, and who and what must be sacrificed to do so. Refusing to choose between the story I lived or the one I’ve read, in the end, I’m casting my vote to proudly hold them together.

Comments are closed.