My evocative detour to West Point and its storied military museum.

By James Long

It’s an imposing site. Whenever I take the train from Grand Central to visit friends north of New York City, I see the striking architecture situated on the west side of the Hudson River—an assortment of Victorian, Gothic and Tudor styles, its jagged arches, turrets and battlements the fruit of a hallowed devotion.

I’m speaking about the picturesque campus of the United States Military Academy in Orange County. Established in 1802 by President Thomas Jefferson, West Point has been the alma mater of countless military leaders who’ve left an indelible mark in American history.

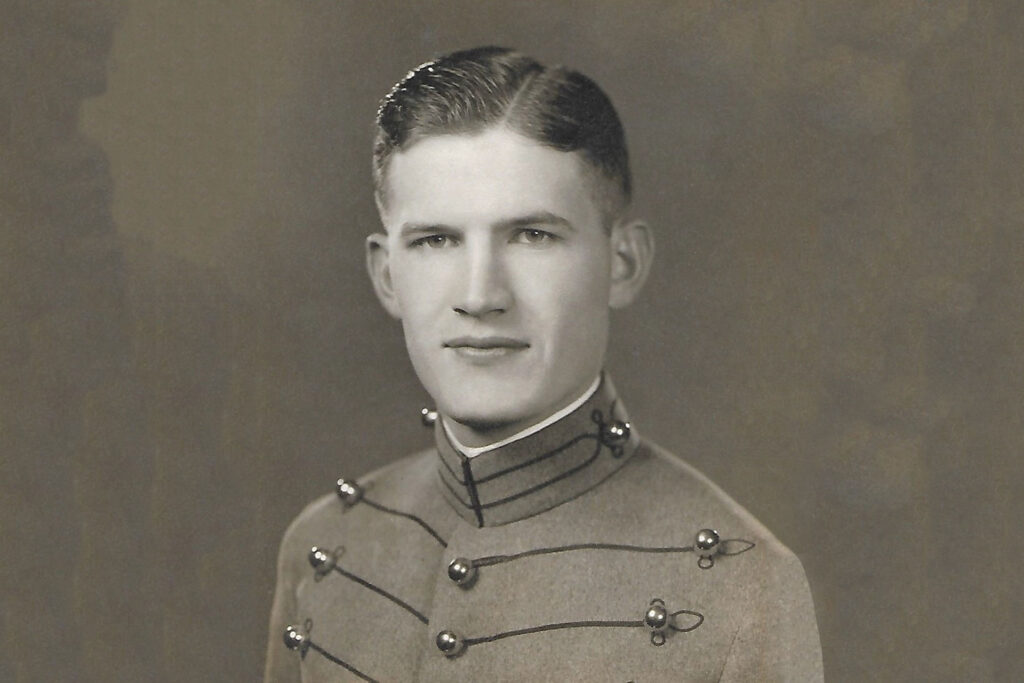

I’ve always had an affinity with the military having grown up a military brat—both my father and oldest brother retired as Air Force colonels, while my godfather and namesake, an Air Force major general, was the executive assistant to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs when I was born. An uncle served in the Army, however. Robert, called “Bobby,” was my mother’s only sibling, two years older, named after his father, the unique Army veteran among an Air Force ménage. Bobby was the impetus for my detour to see friends and visit West Point where he had graduated in 1943.

Exploring West Point, one must begin by visiting its showcase—the West Point Museum, in Olmsted Hall, open to the public. Passing through its grand entrance, this oldest of federal museums expands on West Point’s history and its illustrious graduates—the conflicting loyalties represented by its former superintendent Robert E. Lee, future presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Dwight D. Eisenhower and Gulf War commander Norman Schwarzkopf are among its alumni. There are more than 60,000 artifacts among its four floors and six galleries, a history of warfare ranging from Stone Age clubs and ancient Egyptian weaponry to signature arms—Napoleon’s sword!—as well as defenses used in modern US wars—artillery pieces, a World War I tank, an eye-opening full-sized replica of the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan and myriad automatic firearms. Battle dioramas are intertwined with historically important paintings and sculptures that lend a patient and artistic thoroughness.

One particular display gave me pause—the uniforms worn through the years by cadets, a poignant reminder of the thousands of young men and, eventually, women who spent character-building years at West Point marking their relationship in the destiny of the nation.

I thought of my uncle—how Bobby grew up in rural Tennessee and made his way to a congressional appointment at West Point. After graduating, having already received his pilot’s wings, Bobby was soon transferred to a combat unit overseas—the 358th Fighter Group—which played a critical role in the liberation of France in World War II. Returning from a mission on New Year’s Eve, 1943, Bobby’s P-47 fighter aircraft ran out of fuel and crashed landed in Southern England. He survived, but with near fatal injuries, returning to the US for treatment. After a lengthy hospitalization, remarkably, Bobby returned to full flying status. He’d made it through the war after all.

Then, on August 1, 1947, on the day President Harry Truman established Air Force Day (the precursor to our current Armed Forces Day), honoring “the personnel of the victorious Army Air Forces,” during a commemorative air show in Jamaica, flying the only fighter in the show, Bobby completed the second roll of his aircraft. His P-47 lost speed, stalled and crashed. Captain Robert H. Fautt, Jr., 29, was killed instantly.

Museums are places we visit to connect—with history, with art and culture, with the stories and shared experiences of humankind. The West Point Museum—and its compelling adjacent Visitors Center—are exemplary in that regard with fascinating artifacts. I’d highly recommend a visit. Museums are also a repository for memories, a place for reflection, a break from a breakneck world, allowing us to explore deeper questions and more soulful meanings.

As I left the West Point Museum, while walking along the campus edge and its spectacular views overlooking the Hudson River, I thought of the uncle I never knew—how handsome Bobby must have looked in his cadet uniform, picked on as a “plebe,” returning the favor as a “firstie.” I pictured him with his best buddies, secreting away for a night in wartime Manhattan, with other uniformed men and women in the streets, the same streets where I witness US Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard service members during NYC’s legendary “Fleet Week.”

I couldn’t help negotiating in my mind, however, what it was all for. From all the early and modern weapons of war I’d just seen, it’s impossible to shy away from the complexities a war museum brings to bear. Indeed, I’ve visited the Vietnam Military History Museum, in Hanoi, and more than a few captured American artifacts on display present quite a dispiriting perspective.

“We learn that the soul of fate is the soul of us,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson. “All the toys that infatuate men and which they play for…All the drums and rattles by which men are made willing to have their heads broke…are led out solemnly every morning to parade.” As I resumed my journey on the train to see friends, looking again at West Point from across the Hudson, I saw another parade, those of its current class of cadets drilling in formation on its grounds. And I felt grateful.

Comments are closed.