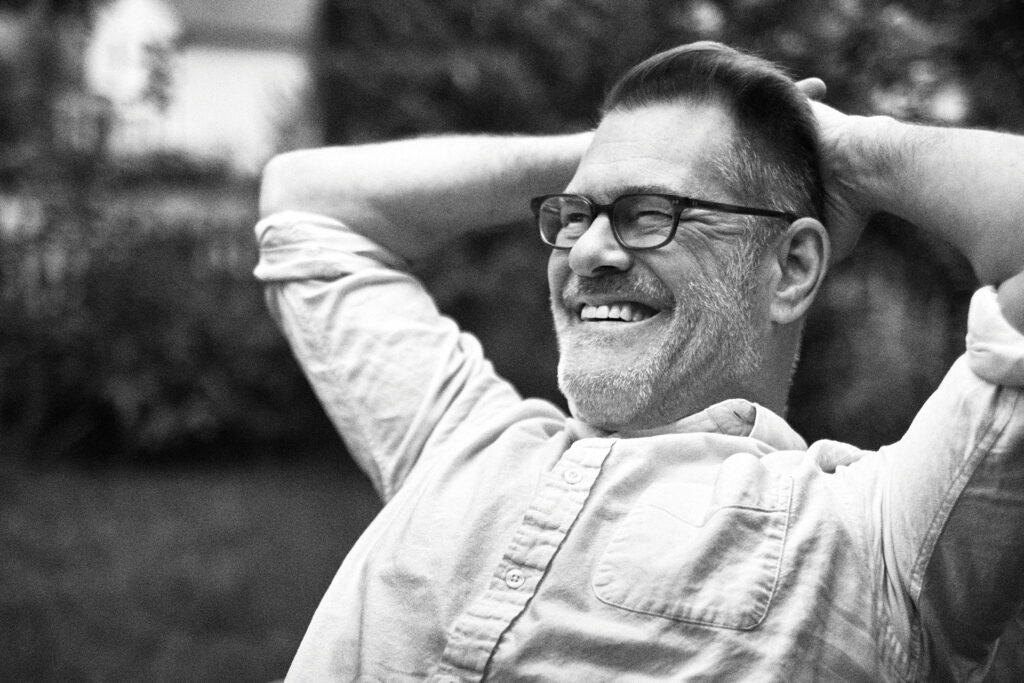

The multiple CFDA-winning designer heads Marist College’s celebrated fashion department and lands safely in Rhinebeck. Don’t call it a comeback. Exactly.

By Hal Rubenstein

Photographed by Fahnon Bennett

On a balmy day in the fall of 1991, I was slumped in my chair behind my desk at The New York Times where I was Men’s Style Director bemoaning a morning spent looking at three men’s collections devoid of ingenuity, individuality or sensuality. Oh, they were perfect if you wanted to look like a banker or a new associate attorney on the hit television series L.A. Law. Despite Gianni Versace’s deliberate objectification of the male torso, the fluidity Giorgio Armani had applied to suitings and the languid come-hitherness infusing every stitch of Dolce and Gabbana, American designers, with one major exception, were still clinging to the stalwart, Man In The Grey Flannel Suit silhouette that had straight-jacketed menswear for decades. The only major US designer leading the rebellion was Calvin Klein, who never met a regimental tie he liked.

Deflated after enduring the morning’s blather about clothes that didn’t warrant a conversation, I was contemplating leaving early when my phone rang (back in ’91 you actually answered your calls and verbally communicated). The voice on the other end was sonorous, intense and ever so slightly seductive. “Hello, my name’s John Bartlett and I’ve produced my first capsule collection of menswear and I’d love for you to come see it.” I hesitated, but the voice was undeniably intriguing. I responded that I was free now if he was prepared to present it. Bartlett said, “Come anytime,” so I headed downtown to his Manhattan apartment on 12th Street in Greenwich Village to meet the new designer and see his stuff. What John (We’ve known each other for three decades so I don’t feel the need to be so journalistically formal) pulled out of trunks and his closet turned my day around. The stuff was good. Really good.

A Harvard graduate who got his degree in sociology, John Bartlett became fascinated by clothes when he moved to New York City, so he enrolled in the Fashion Institute of Technology to learn sewing, sketching and pattern making. However, regardless of what his teachers taught him, as well as his stints following graduation assisting several fine non-traditional designers, Willi Smith, Ronaldus Shamask and Bill Robinson, John’s previous major at Harvard, as well as his own assured self-awareness, were significant influences in his forming his design aesthetic. Though his clothes didn’t follow the risqué tease of Versace, or the sloppy kiss beckoning of D&G, there was something singular and refreshing about the young designer’s eagerness to provoke and indulge the American male’s repressed urge to revel in his own bravado. If you want proof of this bravado’s prevalence and how resplendently it has now blossomed, get on TikTok and view the parade of self-satisfied shirtless young men with rockin’ bodies showing off while proposing to teach you the same exercises for six packs and bulging biceps that were cover lines in Men’s Health 15 years ago. By the way, you will not catch any woman doing the same thing. Not one.

What made John Bartlett’s collections so tantalizing was that the base of his aesthetic is deceptively preppy; so, on a hanger, the clothes appeared unthreatening and familiar. Only when these garments were on your body, and you looked in a three-way mirror (everyone should have one), did you realize how the sly suggestiveness of his designs, the realignment of proportions and penchant for more tactile fabrics, fed the ego. Seeing yourself in his clothes was like getting a pep talk from your best friend. They gave men, even those who normally lack confidence, license to swagger. For this skill, the designer pulled an industry coup in 1997, winning the CFDA (Council of Fashion Designers of America) award for Best Newcomer in Menswear as well as the one for Best Menswear Designer simultaneously. That’s quite the feat.

Bartlett was also one of the first designers to take on the nascent interest in clothes that incorporate sexual fluidity. When he launched his women’s line in 1998, he named the collection Butch/Fem and it handsomely blurred the lines between menswear and womenswear without compromising a woman’s sexuality and celebrities lined up to show off his work, including Janet Jackson, Jennifer Lopez, Sarah Jessica Parker and many more. He has had his own brick-and-mortar stores, collaborated with large brands such as Bon-Ton, Ghurka, Liz Claiborne and Byblos and drew accolades for his savvy reimagining of the famed Hush Puppy loafer.

But more recently the talented designer’s focus has been less on sensuality and more on sustainability, working only with organic and recycled materials, eschewing animal skins and establishing his own nonprofit Tiny Tim Rescue Fund, which raises money for independent shelters and the medical care needed to help these dogs and cats find permanent homes.

Bartlett’s restless, exuberantly sustained desire for exploration has now led him—after a lifetime of exhilarating highs and devastating lows—to a surprising yet not illogical next role. In 2020, he was selected to lead Marist College’s award-winning fashion program, which not only trashes the adage that those who can’t do teach but has given Bartlett an opportunity to not just impart his experience and wisdom of an industry that has had to radically change in recent years, but to listen and learn from a generation that helped instigate that change, since youth views style, beauty and attraction from a very different vantage point. And, for most of his students, a new outfit isn’t necessarily what they believe matters most.

So how does it feel to be on the other side of the lectern? Do you see yourself in your students?

The fact that I’m teaching a course called Fashion and Social Justice immediately notes the dramatic difference. When I was at Harvard studying sociology, we thought about race, but we were exploring other things. Business was booming, we were exploring new attitudes toward sexuality, a heightened awareness of body consciousness, how to achieve an ideal. Today’s students want no part of that. For them, it’s all about body positivity, creating collections for non-binary people, making clothes that work on curvier plus-sized women, designing for the disabled. My students seem to always be thinking about sustainability, where things are sourced, how do they grow. Everything they do is seen through the eyes of social justice.

What do you think sparked their intense interest in not just being satisfied with flattering design?

Social media had a lot to do with it. The Black Lives Matter movement had an enormous ripple effect on all minorities. But the conversation wasn’t confined to influencers, though they matter a great deal. A lot of people have been talking about it. Even Vogue had to change. Our faculty now makes a communal effort to go back and look at our lectures and make sure the information about fashion that we present is as diverse and as global as possible.

Because we’ve crafted a niche-centric culture, it’s always been easy for us to look at fashion as a stand-alone craft. But no aspect of our culture ever exists in a vacuum.

My course starts in the mid-19th century, then gains momentum with the Suffragette movement at the turn of the century, but the connection starts to get more exciting starting in the ’60s with protest fashion, clothing that reflects anti-war and reproductive rights, then the Black Panthers, Katherine Hamnett’s message T-shirts, Act Up Silence=Death T-shirts during the AIDS pandemic. I identify with the struggle because when I was their age, I was grappling with how to live as an out gay man.

Did you have a difficult time coming out?

Harvard was homophobic, not that that was unusual at the time, but it became easier when I started meeting guys my age. When I started going to FIT, I didn’t know if I was going to go into design or marketing, but I knew I always had to find something to wear to The Tunnel or The Palladium (Manhattan mega discos in the ’90s).

What made you shift your focus from sociology to fashion?

I always loved clothing. My mom would get Vogue and I’d spend hours studying it. When I got my driver’s license, the first place I went to was The Salvation Army because vintage clothes seemed more distinctive to me and as a gay man I found it an incredible way to identify myself. Clothing is always telling a story. When I started working for Ronaldus Shamask and Bill Robinson, I just wanted to live and breathe fashion.

But when you started designing on your own, in an industry known for its way more than average density of gays at every level, were you surprised at the collective skittishness toward both your openness about being gay and how that influenced your pieces?

Happily, it’s evolved. There was a moment when I started showing more provocative collections, there were gay men who were buyers who told me the clothes were too gay. Of course, you could show a woman in a thong, and nothing happened. Gianni Versace moved the needle more than anyone. I’m not what you call fluid. But fashion is certainly that now.

You created another set of ripples when you embarked on another alternative pursuit.

I read actress Alicia Silverstone’s book, The Kind Diet, and I suddenly had an “a-ha” moment, not because of her recipes but due to her love of animals and her recoil at factory farming. It also coincided with my rescuing a dog from the North Shore Animal League (in Long Island, NY). That dog, Tiny Tim, changed my life.

Wow, can you tell us how?

The more I visited the shelter where these people save these wonderful creatures, the more I got pulled into that world. I started meeting with the “Vegan Mafia,” PETA and The Humane Society. The fashion industry is built on the leather industry, since its largest source of income comes from accessories. I just didn’t want to make clothes that involved animal suffering. I remember being on the board of the CFDA at the time, and I came out about this definitively at a meeting and it was a very awkward and uncomfortable moment. My fellow board members looked at me and rolled their eyes.

And yet now, fur has pretty much been banished from the runway. More designers—and importantly customers—aren’t dismissing substitutes. In food, we have The Impossible Burger. You just got there a bit ahead of the pack.

Me and Todd Oldham (another CFDA award-winning designer from the ’90s who was the first to eschew animal skins from his runway a decade before Stella McCartney). Now, the industry is trying to come up with plant-based leather products that aren’t merely substitutes but also excel in performance. I’m very inspired by new companies that are creating clothes with an awareness of who’s making these garments and how big their carbon footprint is. And we can no longer ignore that there’s a rapidly growing number of consumers who, like my students, really care about sustainability.

Your position at Marist in Poughkeepsie required you to move from Manhattan to the Hudson Valley. How radical a change has that geographical shift been for you?

I love the house I’m in in Rhinebeck. I didn’t want to be too rural. That wouldn’t be a good look for me [Laughs]. I wanted a sense of the country, but I still needed to see a neighbor, especially after John died (Bartlett’s husband John Esty died of prostate cancer at age 56) and I spent the pandemic alone, which sucked, except for being with my dogs—I couldn’t be that isolated.

Did losing John help prompt a change of scenery and direction?

Perhaps. I did a lot of bereavement work when he passed. I couldn’t find a gay, male bereavement group in New York City, so I collected other widowers, and we formed a new group. We keep bringing in new people. I also credit the Zen Center for Contemplative Care for their help. And I joined a 12-step program and feel sober and solid. It’s taken a long time. Five years.

Are you willing to put yourself out there again?

I have. I’ve dated here and there. I spend a lot of time with friends. And I recently met a lovely man, Jade Barbee, who lives in Vermont, is really nice and is an amazing vegan cook. In fact, we’re boyfriends.

Do you still follow current fashion?

I recently did a recap of the latest New York Fashion Week for my students. I love the way people are working with sheer materials and transparency, reviving some ’90s trends I’ve always liked. And I love the clothes of LaQuan Smith which are so sexy and beautifully made and the work of Peter Do who approaches minimalism in a new way.

Do you ever get the urge to design again?

I’ve started working on a group of accessories. I love fitted vests. I wear them all the time. I prefer short sleeve military shirts and boxer shorts. I’m looking to have it produced. I’m also working with a group of women called Unshattered.org located in Hopewell Junction, who are all former victims of addiction forging a future for themselves by creating very handsome sustainable handbags. (Unshattered.org is a 501(c)3 organization with 100 percent of their profits going to help other women find “pathways to sustained sobriety and economic independence.”)

I’m also working with a couple of start-ups such as Made X Hudson, a small garment manufacturer trying to bring jobs to the Hudson Valley. I’m making quilts—I have such an endless supply of scraps from all of my collections—I can make them from start to finish. I’d like to do small runs of things or a pop-up store and raise money for shelters for trans youth such as the one in Dutchess County, or for animal organizations including the SPCA in Poughkeepsie.

You know, John, it really seems like you’re happy here.

I sometimes miss the energy of New York City, the experience of running into people on the street you haven’t seen for years or just yesterday. I wish my students would rely less on social media and who their favorite top ten influencers are and come into town, go into a store and touch fabrics and look at garments and turn them inside out. But I definitely see where I am now as my next career. I’m inspired by the fact that Marist College is a gem because it isn’t just teaching fashion and design but insists students get a rounded liberal arts degree. My friends Upstate, as everyone who lives here knows, are all spread out, but I enjoy exploring towns including Woodstock, Austerlitz and Catskill. I love coming home and making dinner. Walking my Burnese mountain dog on the same hike every day. So many people have moved up here and started a new life, just like me. The thing is, it’s really a charming way to live.

Comments are closed.